ERP System in Supply Chain Management: What It Is, How It Works, and How Manufacturers Use It to Improve Performance

Today’s supply chains are interconnected, fast-moving, and constantly changing—especially for automotive suppliers managing daily releases, tight delivery windows, and customer-specific shipping requirements. When demand, inventory, production, and shipping live in disconnected systems (or spreadsheets), you get delays, manual rework, preventable errors, and blind spots that show up fast in missed OTIF targets, excess inventory, and margin erosion.

That’s why an ERP system in supply chain management is no longer a “back office” tool—it’s the operational hub that connects planning, procurement, production, inventory, and logistics in one controlled flow of data. In this article, we’ll answer what is ERP in supply chain management, explain how an ERP system in supply chain improves visibility and execution from demand signals through shipment confirmation, and outline the key capabilities to look for (including compliance-critical areas like EDI/ASNs, labeling discipline, and audit readiness for frameworks like MMOG/LE and IATF 16949).

After three decades of working with automotive production part suppliers, AIM consistently sees these challenges emerge when ERP systems aren’t designed to enforce automotive execution rules.

What Is ERP in Supply Chain Management?

When people ask “what is ERP in supply chain management?” they’re really asking what connects planning to execution—without relying on spreadsheets, emails, and disconnected tools. ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) is the system that centralizes the data and workflows your teams use to run the business: purchasing, inventory, production, order management, shipping, invoicing, and reporting.

In other words, an ERP system in supply chain management becomes the operational “hub” where supply chain decisions (what to buy, build, move, and ship) are translated into controlled transactions (purchase orders, work orders, pick/pack/ship, invoices, receipts, and adjustments). Instead of each department working off its own version of the truth. For automotive suppliers, ERP provides a shared system of record that governs customer releases, production execution, shipping, and financial reconciliation.

ERP system in supply chain vs. “supply chain software” (SCM, WMS, TMS)

It helps to clarify what an ERP system in supply chain does—and what it doesn’t do on its own.

- ERP is usually the backbone for end-to-end business processes (order-to-cash, procure-to-pay, plan-to-produce). It holds master data (items, customers, suppliers, BOMs, routings, costs) and the official transactions that accounting and operations rely on.

- SCM planning tools (forecasting, demand planning, network planning) can be excellent at scenario planning and optimization—but they still need clean execution and “system truth” to make plans real.

- WMS systems specialize in warehouse execution (directed picking, slotting, wave planning, labor management, advanced scanning flows).

- TMS systems specialize in transportation execution (load building, carrier selection, tendering, tracking, freight audit).

In a high-performing environment, these systems work together. But the ERP is often where companies anchor the workflow because it ties operational execution directly to financial impact (cost, margin, working capital) and provides the governance layer for data accuracy.

How an ERP system in supply chain management works in practice

A simple way to understand an ERP system in supply chain management is to follow the lifecycle of a single demand signal:

- Demand enters the business (customer orders, forecasts, EDI releases, blanket orders, program schedules).

- Planning translates demand into supply actions (MRP, reorder points, min/max, capacity signals).

- Procurement and production execute

- Buyers create and manage POs, confirmations, lead times, and supplier performance.

- Production teams convert requirements into work orders, routings, labor capture, and WIP movements.

- Inventory is updated in real time as materials are received, moved, consumed, produced, and shipped.

- Fulfillment happens with control (allocation, pick/pack, shipment documentation, customer-specific requirements, billing).

- Finance and reporting reflect reality (COGS, inventory valuation, variances, margin, OTIF performance dashboards).

This is the core value: ERP turns supply chain activity into controlled, traceable transactions—so you can measure what happened, explain why it happened, and improve it.

The real differentiator: data integrity + process control (not just “features”)

Most ERP platforms claim they support supply chain management, but supply chain leaders know the truth: outcomes depend less on a feature checklist and more on whether the system consistently enforces the rules that keep execution clean. An ERP system in supply chain management has to do more than “store data”—it has to protect data quality and standardize how work gets done, day after day, across every department that touches demand, inventory, production, and shipping.

In practice, that means the ERP must help you maintain accurate item masters (units of measure, pack quantities, lead times, planning parameters), reliable BOMs and routings (so MRP and scheduling don’t become garbage-in/garbage-out), and consistent supplier/customer records (ship-to rules, tolerances, labeling and shipping requirements). It also needs to reinforce inventory discipline through location control, cycle counting, and the right lot/serial traceability where required—while giving teams clear exception visibility through alerts, dashboards, and workflows when demand or supply changes.

Because supply chains rarely fail in dramatic ways first—they fail in small ways repeatedly: a lead time that’s wrong, a pack quantity that isn’t enforced, a shipment that goes out with incomplete reference data, or a receipt that doesn’t hit the right lot/location. Over time, those “small” misses show up as late shipments, expedite costs, excess inventory, and avoidable chargebacks. Often costing suppliers thousands per month in premium freight and chargebacks—exactly the problems an ERP system in supply chain is supposed to prevent.

Automotive reality check: where “generic ERP” often needs help

If you’re in automotive (Tier 1–3), the question isn’t just “does the ERP support supply chain management?” It’s “does the ERP support automotive supply chain execution without heroic workarounds?” Automotive programs move fast, customer rules are strict, and the penalties for getting execution wrong show up quickly in scorecards, premium freight, and chargebacks.

That’s because automotive supply chains often include high-frequency schedule changes (daily shipping schedules and shifting releases), strict customer compliance requirements (ASNs plus customer-specific shipping and pack rules), and labeling plus scan verification needs (AIAG-compliant labels, destination/serial rules, and dock-level validation). On top of that, many suppliers must manage cumulative (CUM) tracking and release accounting so they can reconcile what the customer says they required/received versus what the supplier shipped—without turning every discrepancy into a manual fire drill.

This is why successful automotive suppliers either choose an automotive-optimized ERP or extend their ERP with an automotive-specific execution layer purpose-built for EDI, labeling, shipping validation, and cumulative tracking. In automotive, the “last mile” of execution detail is where compliance is won or lost—and it’s also where a generic ERP often needs help to consistently deliver OTIF performance.

Now that we’ve answered what is ERP in supply chain management, the next step is to break down where ERP drives results across the supply chain—planning, sourcing, production, inventory, logistics, and performance analytics—and which capabilities matter most in each area.

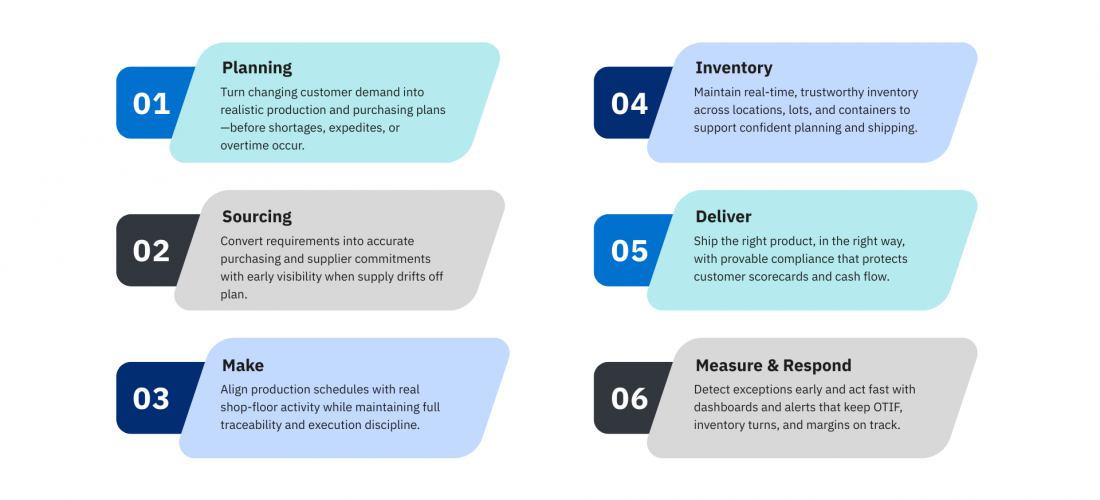

How an ERP system in supply chain management connects planning to execution (plan → source → make → deliver)

If you’re asking what is ERP in supply chain management, the most practical answer is this: it’s the system that connects demand signals to day-to-day execution, so every department is working from the same rules, the same data, and the same priorities. In other words, an ERP system in supply chain isn’t just tracking activity after the fact—it’s coordinating the work as it happens, across purchasing, production, inventory, shipping, and finance.

Planning: turn demand into a feasible plan (MRP + capacity)

At the planning level, an ERP system in supply chain management should translate customer demand into actionable requirements—what to make, what to buy, and when. That’s where capabilities like forecasting, safety stock policies, lead times, MRP, and capacity planning become mission-critical. If planning is done outside the ERP (or based on stale masters), you end up with “plans” that can’t be executed—resulting in expediting, overtime, missed shipments, and bloated inventory.

Why this breaks down in automotive environments

In automotive, planning gets even more dynamic because demand can change frequently and in multiple formats (forecast vs. ship schedules vs. sequenced demand). When the ERP is configured correctly, demand changes become controlled adjustments—not fire drills that ripple through every department.

Sourcing: convert requirements into clean purchasing and supplier performance

Once the plan is credible, ERP should automate how supply gets secured: purchase orders, supplier releases, order acknowledgments, delivery tracking, and supplier performance reporting. This is where the supply chain either stays stable—or starts to wobble—because sourcing problems don’t usually show up as one big failure. They show up as partial receipts, late arrivals, substituted materials, and mismatched pack quantities that quietly break schedules and inventory accuracy.

A strong ERP workflow here doesn’t just “create POs.” It enforces that suppliers, items, lead times, and receiving rules are correct, and it gives you early visibility when reality diverges from plan—so you can respond before OTIF and service levels take the hit.

Make: connect the schedule to the shop floor (and keep it traceable)

Execution is where supply chain strategy becomes reality. ERP must support routings, work centers, labor reporting, scrap/downtime capture, and WIP visibility so production is scheduled and managed based on facts, not assumptions. When shop-floor transactions are delayed or inconsistent, the entire supply chain becomes a guessing game: planners don’t trust inventory, shipping can’t commit confidently, and leadership loses the ability to protect margin from rework and expedite costs.

For automotive production part suppliers, traceability often isn’t optional—it’s tied to customer expectations, audit readiness, and containment speed when issues occur. A properly configured ERP captures the “who/what/when/where” of production and movement without making operators jump through hoops, so traceability strengthens execution instead of slowing it down.

Inventory: maintain real-time accuracy across locations, lots, and containers

Inventory is the connective tissue of the supply chain, and it’s also where disconnected systems do the most damage. ERP should provide real-time inventory transactions, location control, cycle counting discipline, and the ability to track lot/serial where required—because planning and shipping decisions are only as good as inventory truth.

This matters even more in high-velocity environments (multiple shifts, multiple warehouses, frequent shipments). When ERP enforces location and transaction discipline, you reduce shortages, prevent overbuying, improve inventory turns, and stabilize lead time performance.

Deliver: ship correctly, prove compliance, and protect cash flow

Delivery is where many supply chains “win or lose,” because this is where customer experience, scorecards, and chargebacks get decided. ERP must support order management, packing, shipment documentation, and invoicing—but in industries like automotive, that’s not enough on its own. Automotive shipping often requires customer-specific pack rules, scan verification, and electronic confirmations (like ASNs), plus release and cumulative (CUM) reconciliation so you can prove what was required versus what was shipped/received.

It’s also why many automotive suppliers keep ERP as the system of record, but add an execution layer for automotive-specific shipping control—particularly for EDI schedules and compliance processes. Inbound demand can arrive through multiple automotive transaction types (for example: 830 material releases, 862 shipping schedules, 850/860 purchase orders/changes, and 866 production sequencing), and the supply chain system has to normalize that demand and drive clean execution without manual rekeying.

For AIM customers, this is exactly where AIM AutoSys, AIM AutoCOR, and AIM Vision ERP tend to deliver outsized value: ensuring the last-mile execution details (EDI-driven releases, AIAG-compliant labeling, shipment validation, and cumulative tracking) stay aligned with customer rules—helping suppliers ship right the first time, protect OEM scorecards, and eliminate last-minute compliance fire drills.

Measure and respond: dashboards + exceptions keep the supply chain stable

Finally, ERP needs to make the supply chain manageable when conditions change—which means actionable exception visibility, alerts, dashboards, and workflows (not just reports that get reviewed after the damage is done). The goal is fast detection and fast resolution: a late supplier receipt, a sudden demand spike, an inventory discrepancy, or a schedule change should trigger clear actions—not confusion about whose numbers are correct.

When those exception loops exist, teams can protect the KPIs that executives care about most—OTIF, lead time, inventory turns, and margin—because the organization is responding to real-time signals instead of yesterday’s surprises.

This is why many automotive suppliers anchor governance in ERP, then extend execution with automotive-specific systems that enforce EDI, labeling, and shipping discipline.

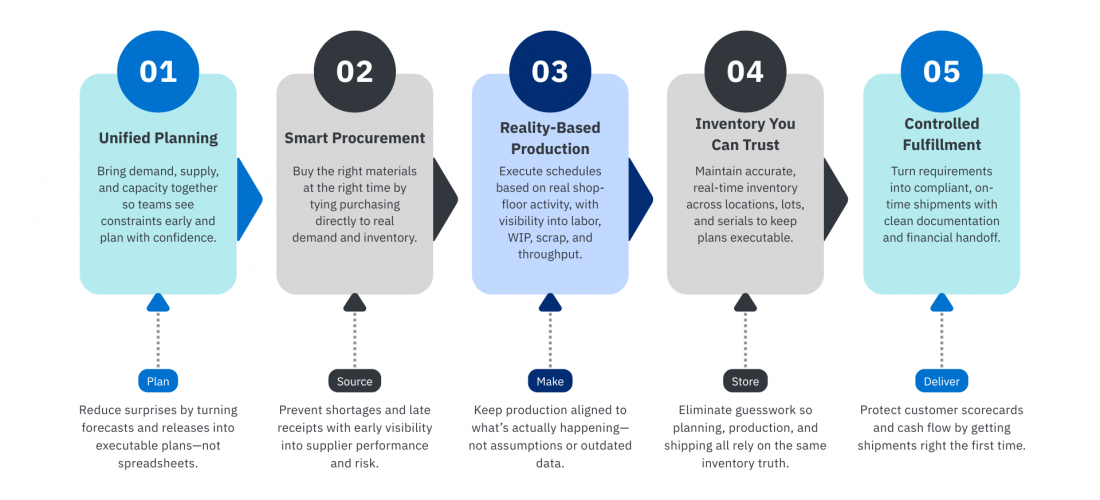

How an ERP system supports supply chain management end to end

When people ask “what is ERP in supply chain management?” the most useful answer is practical: it’s the system that connects planning to execution, so demand signals don’t die in spreadsheets or get re-keyed into four different tools. A strong ERP system in supply chain management turns forecasting and customer requirements into purchase orders, production schedules, inventory movements, shipments, and invoices—while maintaining the controls that keep the data clean and the process repeatable.

Plan: demand, supply, and capacity in one place

Supply chain performance starts with planning accuracy and response speed. In an ERP-driven environment, demand (forecasts, customer releases, sales orders) feeds planning engines like MRP and capacity planning so teams can see constraints early—before shortages become expedites. This is where lead times, safety stock, planning parameters, and “what-if” scenarios matter, because they directly influence service levels, inventory turns, and schedule stability. Without ERP-centered planning, it’s easy to end up with disconnected forecasts, missed constraints, and reactive decision-making that inflates costs.

Source: procurement that’s tied to real requirements

Sourcing isn’t just about issuing POs—it’s about buying the right things at the right time based on real demand and real inventory. An ERP system links requisitions and purchase orders to MRP signals, tracks supplier performance, and captures receiving and discrepancies in a way that updates availability immediately. That visibility helps prevent the classic supply chain failure pattern: parts “available” on paper that aren’t actually usable on the floor, or components arriving late with no early warning until production is already impacted.

Make: production execution that reflects reality, not assumptions

On the manufacturing side, ERP becomes the coordination layer between what you planned and what you can actually build today. Work orders, routings, labor reporting, scrap, and WIP movement all need to reconcile with inventory and schedules in near real time—especially in repetitive environments where small variances add up fast. The more your shop floor signals (and quality events) flow into ERP, the more accurately you can protect lead time, reduce firefighting, and keep customer commitments realistic.

Store: inventory accuracy as a supply chain capability

Inventory is where most supply chain “truth” is won or lost. A supply-chain-ready ERP enforces disciplined receiving, location control, cycle counting, and (when required) lot/serial traceability—so planners aren’t trying to run MRP on unreliable balances. When inventory accuracy is high, everything improves: less premium freight, fewer shortages, better scheduling, and fewer customer disruptions. When it’s low, every downstream process—shipping, production, purchasing—pays for it.

Deliver: order management, fulfillment, and logistics execution

This is where an ERP system in supply chain proves whether it can support your service goals. Order management and fulfillment must translate requirements into pick/pack/ship execution with the right packaging rules, documentation, and shipment confirmation—then flow financials cleanly into invoicing. In many industries that’s already complex; in automotive, delivery execution often includes customer-specific shipment rules, rapid schedule changes, and compliance-heavy processes (labels, ASNs, and reference data) that can break “generic” workflows if they’re not designed for it.

Where ERP fits in the supply chain tech stack (and why it matters)

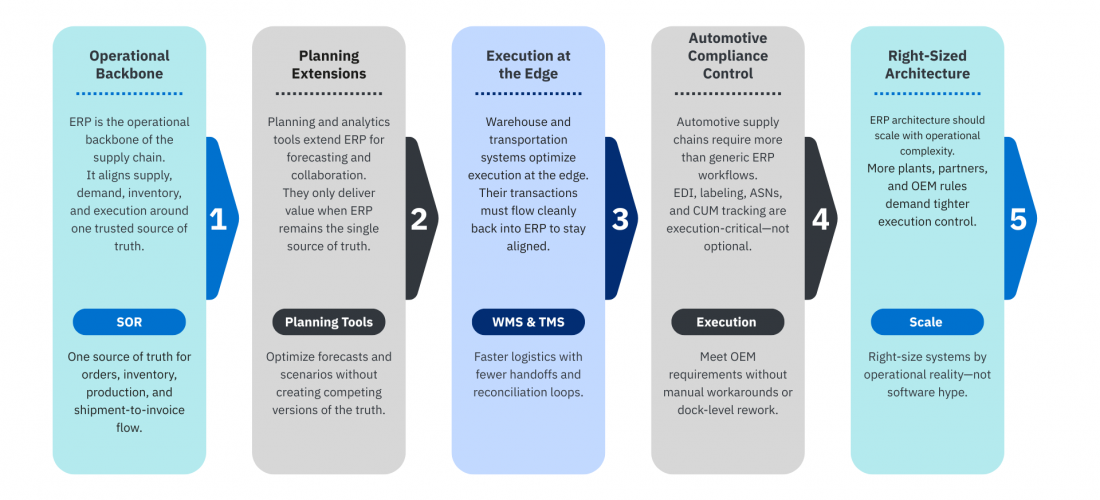

When teams search “what is ERP in supply chain management,” they’re usually trying to answer a practical question: Which system should be the source of truth for supply, demand, inventory, and execution—and what else do we still need? The most reliable approach is to treat an ERP system in supply chain management as the operational backbone (master data + transactions + financial truth), and then layer in specialized tools only where they add measurable value—without breaking data integrity.

ERP is the system of record for supply chain execution

An ERP system in supply chain isn’t just a database—it’s the platform that enforces the “rules of the road” across planning and execution. It’s where customer demand becomes real orders, where inventory movements become auditable transactions, where production consumes material and creates finished goods, and where shipping triggers invoicing and margin reporting. In other words: the ERP is what turns supply chain activity into controlled, traceable process—so you can trust metrics like inventory turns, lead time, and OTIF.

SCM tools typically extend planning and collaboration outside the ERP

Many organizations add supply chain planning (SCP), demand planning, supplier collaboration, or advanced analytics tools on top of ERP—especially when forecasting, multi-echelon inventory optimization, or scenario planning becomes complex. These systems can be powerful, but they only work when the ERP data foundation is clean and when the integration is designed to prevent duplicate truths (two item masters, two “available inventory” numbers, two order states). If the ERP and the planning tools disagree, execution teams will revert to spreadsheets—fast.

WMS and TMS are often “edge execution,” integrated back into ERP

Warehouse Management Systems (WMS) and Transportation Management Systems (TMS) can drive efficiency for high-volume distribution and complex logistics networks. But they should still post clean, validated transactions back to ERP (receipts, picks, shipments, freight costs). The goal isn’t “more systems”—it’s tighter execution with fewer reconciliation loops.

In automotive, EDI + labeling + release accounting are not optional “extras”

This is where generic supply chain articles often stop short. In the automotive supply base, supply chain execution lives and dies on highly structured customer communication and compliance workflows—especially EDI schedules, shipping validation, and customer-specific labeling.

Automotive suppliers commonly deal with inbound schedule and order transactions like 830 (planning schedule), 862 (shipping schedule), and 850/860 (PO/changes), plus outbound processes that rely on accurate shipping documentation and ASNs. A best-in-class environment consolidates those requirements into a centralized order system and keeps demand continuously updated as new schedules arrive—so the shipping lineup stays aligned to the latest releases.

And because OEMs often manage expectations in cumulative quantities, automotive execution also requires reliable CUM tracking and reconciliation (customer CUM received vs. supplier CUM shipped), including resets and adjustments when discrepancies occur. If your ERP (or connected layer) can’t handle that cleanly, you get “phantom past dues,” avoidable expedites, and customer disputes that show up as scorecard hits and chargebacks.

This is why many automotive suppliers either select an automotive-optimized ERP or keep an existing ERP as the financial system of record while adding an automotive execution layer for EDI, labeling, shipment validation, and release/CUM logic. AIM Vision, for example, is designed specifically for automotive suppliers with embedded EDI logic for hundreds of trading partners and standardized AIAG label formats, alongside supply chain and inventory functionality—so execution and compliance stay connected to the same operational data.

Right-sizing the architecture by complexity (not hype)

In practice, what you need from an ERP system in supply chain management often correlates to operational scale and trading-partner complexity. Smaller and mid-size automotive suppliers may benefit from an ERP that delivers end-to-end control (planning, inventory, production, shipping, and compliance) without requiring a patchwork of bolt-ons. Larger or multi-plant suppliers may standardize on a corporate ERP but still need plant-level automotive execution controls to meet OEM requirements consistently.

A simple way to frame scale—especially for automotive go-to-market and system fit discussions—is by annual revenue tiers (for example: $10M–$50M, $50M–$150M, $150M–$250M, $250M–$500M, and beyond), because each step up typically brings more plants, more trading partners, more schedule volatility, and more compliance surface area.

Now that we’ve clarified where ERP sits (and what it must control), the next step is to break down the specific supply chain workflows an ERP must handle—planning, procurement, production, inventory, shipping, and traceability—and how to evaluate them without getting distracted by feature lists.

What an ERP system in supply chain management actually does across Plan–Source–Make–Deliver

Once you look at an ERP system in supply chain management as the operational hub (not just a financial database), the next question becomes practical: what work should ERP run end-to-end so planning and execution stay aligned? At a high level, what is ERP in supply chain management comes down to one job—turning demand into coordinated actions across purchasing, production, inventory, shipping, and finance, using one shared set of rules and records.

Planning: turning demand into an executable plan (not just a forecast)

In the real world, demand isn’t stable—forecasts shift, customers adjust schedules, and priorities change daily. The ERP system in supply chain is where those changes should translate into updated requirements, updated priorities, and updated commitments. That includes setting planning parameters (lead times, safety stock, order policies), running MRP, and creating a feasible schedule that operations can actually execute. When planning lives in one system and execution lives somewhere else, teams end up “planning twice”—once in spreadsheets and once on the shop floor—with two different answers.

A supply-chain-ready ERP also helps you manage the ripple effect of change. A single demand adjustment should automatically surface what it impacts: raw material requirements, capacity constraints, production start dates, supplier due dates, and customer promise dates. That’s how ERP supports the KPIs leadership cares about (OTIF, lead time, inventory turns)—not by promising perfection, but by making tradeoffs visible early enough to act.

Sourcing and procurement: keeping suppliers aligned to production reality

Procurement is where a lot of supply chains quietly break: purchase orders don’t reflect the latest plan, suppliers don’t have clear requirements, and shortages don’t show up until production is already interrupted. A strong ERP workflow connects planning outputs directly to purchasing actions—suggested POs, reschedules, expedite signals, and supplier delivery performance—so buyers spend less time hunting for problems and more time preventing them.

This is also where supplier collaboration matters. Even if your suppliers aren’t “fully integrated,” ERP should still create consistent communication: accurate PO releases, confirmed due dates, receipt expectations, and clear exception handling when suppliers miss commitments. When ERP is doing its job, it becomes harder for a shortage to surprise you—because it’s flagged as a risk while there’s still time to respond.

Manufacturing and shop-floor execution: keeping the plan honest

A plan is only as good as what actually gets produced. That’s why ERP’s role in supply chain management isn’t just planning—it’s also driving execution discipline. Your ERP should translate demand into production orders (or schedule signals), manage work-in-process, record completions, and reflect yield/scrap so the system’s inventory and capacity assumptions stay grounded in reality.

When production reporting is late or inconsistent, you get the classic supply chain symptoms: inventory that “exists on paper,” shortages that don’t make sense, and constant expediting because the system can’t be trusted. The goal isn’t more data entry—it’s fewer manual workarounds. ERP should make it easy to capture what matters (moves, consumption, completions, downtime reasons where relevant) so downstream processes—shipping, customer service, replenishment—aren’t operating blind.

Inventory and warehouse control: accuracy you can build decisions on

Inventory is the “truth layer” of supply chain execution. If the system doesn’t know what you have, where it is, and what condition it’s in, everything downstream becomes guesswork. A supply-chain capable ERP enforces location control, supports cycle counting, and manages traceability requirements (lot/serial where needed). It should also make it obvious when inventory is at risk: aging stock, nonconforming holds, mismatched units of measure, or allocations that exceed what’s physically available.

This is where many teams feel the difference between an ERP that stores inventory and an ERP that controls inventory. When the system drives disciplined transactions (receipts, moves, picks, ship confirms), planners and operations leaders stop debating the numbers and start improving them.

Order management, logistics, and fulfillment: getting shipments “right the first time”

The most visible moment in the supply chain is shipment. It’s where customers judge performance and where mistakes get expensive fast (premium freight, rework, chargebacks, strained relationships). An ERP system in supply chain management should manage the full order-to-cash execution loop: order requirements, allocations, pick/pack/ship workflows, documentation, shipment confirmation, and invoicing tied to what actually went out the door.

The key is tight linkage between what was promised, what was prepared, and what was shipped. When ERP is working properly, there’s less room for “almost correct” shipments—missing references, wrong pack quantities, partials that don’t match the customer’s expectations, or shipments that get invoiced incorrectly because fulfillment and finance aren’t connected.

Visibility + exception management: the part most teams underestimate

The biggest wins in supply chain often come from handling exceptions faster—before they become late shipments. That means ERP needs real operational visibility: dashboards, alerts, workflows, and roles-based queues that highlight what changed and what now needs attention. A good ERP doesn’t just tell you “something is late.” It tells you why it’s late, what it affects, and what your options are.

This is also where standardization pays off. When the system flags exceptions consistently—supplier delays, demand spikes, capacity overloads, inventory discrepancies—teams can build repeatable responses instead of improvising every day. That’s how supply chains move from firefighting to control.

Where ERP meets real-world execution: from customer release to a compliant shipment

It’s easy to talk about “planning” and “visibility,” but the value of an ERP system in supply chain management is proven (or lost) in daily execution—especially when customer requirements change fast. In manufacturing, supply chain performance is the cumulative result of thousands of micro-decisions: which release is current, what quantity is actually due, what pack rules apply, what must appear on the label, what the ASN must contain, and whether the shipment is “valid” under that customer’s rules.

This is also where many teams realize the difference between an ERP system in supply chain on paper and an ERP that can actually protect OTIF, prevent chargebacks, and keep the dock moving without rework. The system has to translate demand signals into actionable work, enforce customer-specific shipping rules, and produce the compliance outputs (labels, ASNs, acknowledgments) that keep the customer’s receiving process clean.

Inbound demand signals: convert schedule chaos into clean requirements

Customer demand doesn’t arrive as a single, stable purchase order. In automotive and other high-velocity environments, releases change frequently and often come with multiple “layers” of demand (forecast vs. firm vs. sequenced). The ERP needs to ingest those updates, normalize them, and ensure downstream processes (MRP, scheduling, picking, shipping) are always working off the current truth.

If that translation is weak, the supply chain pays for it immediately: planners chase moving targets, production builds the wrong mix, and shipping spends the day expediting “surprises” that were sitting in someone’s inbox or spreadsheet.

Order management: enforce customer-specific rules before they hit the dock

Once demand is inside the system, the next challenge is not simply “create an order.” It’s to preserve and apply the customer’s rules all the way through execution—pack quantities, ship windows, ship vs. delivery logic, ship-to nuances, dock codes, handling codes, reference numbers, and any additional fields your customer expects to see carried forward into paperwork, labels, and the ASN.

This is the point where a lot of “ERP supports supply chain” claims break down. If the rules live in tribal knowledge (or a binder) instead of the workflow, you get predictable failure modes: partials shipped incorrectly, the right parts shipped to the wrong dock, or labels that pass internal checks but fail the customer’s scan/receive process.

Outbound execution: labels + scan verification + ASNs are the compliance trifecta

Shipping is where supply chain compliance becomes measurable. You can have perfect planning and still get penalized if the final steps aren’t controlled.

A supply-chain-ready ERP must support:

- AIAG-compliant labeling and customer-specific label variations (not just “print a label,” but print the right label for that ship-to, pack scenario, and destination logic).

- Scan-to-ship verification so what you intend to ship matches what you actually ship—before the truck leaves.

- Accurate ASN creation that mirrors the shipment exactly, including pack structure, serial rules (where required), and customer reference data—so your customer can receive without exceptions.

This is also why some manufacturers operate with an ERP as the system of record, but rely on an execution layer to enforce trading-partner logic at the edges (EDI, labeling, shipping validation). That’s not redundancy—it’s risk control.

Release accounting and CUM tracking: protect margin by preventing disputes

A major blind spot in generic supply chain conversations is that “what we shipped” and “what the customer believes we shipped/received” can diverge—quietly at first, and then painfully during reconciliation.

That’s why mature supply chain operations treat cumulative tracking and release accounting as a first-class process. If the ERP can’t reconcile release history, CUM positions, and customer-reported figures (and handle resets/adjustments cleanly when they occur), you wind up spending time on manual investigations, disputing receipts, and absorbing avoidable chargebacks.

In other words, what is ERP in supply chain management at the executive level? It’s the system that must make demand, production, inventory, and shipment truth auditable—so disagreements don’t turn into margin leaks.

Practical takeaway: ERP is the hub—but execution rules decide outcomes

At this stage, the core insight is simple: an ERP can absolutely be the operational hub of supply chain management, but only if it enforces the execution details that customers score you on. That enforcement can be native (inside an automotive-optimized ERP) or achieved by integrating a purpose-built supply chain execution/compliance layer with your existing ERP.

For automotive suppliers, this is exactly where AIM fits:

- AIM Vision ERP supports end-to-end execution with embedded automotive EDI, labeling, and supply chain controls.

- AIM AutoSys and AIM AutoCOR strengthen supply chain execution for teams that keep their existing ERP (including Epicor environments) but need tighter control over EDI, labeling, shipping validation, and cumulative tracking.

Where ERP actually moves the needle across the supply chain

When people ask “what is ERP in supply chain management?” the most useful answer isn’t a definition—it’s a description of what the system controls. An ERP system in supply chain management becomes the place where demand, supply, production, inventory, and fulfillment stop living in separate spreadsheets and start operating like one set of rules. In other words, the ERP system in supply chain isn’t valuable because it stores data—it’s valuable because it turns data into decisions that can actually be executed.

Turning demand signals into a schedule you can run

Supply chain performance breaks down fast when demand is “known” but not operationalized. A customer release, forecast update, or schedule change is only helpful if it turns into a clear plan that purchasing, production, and shipping can follow without reinterpretation.

A strong ERP foundation translates demand into time-phased requirements, aligns it to lead times and constraints, and keeps that plan current as the world changes. Instead of reacting to “what changed” in three different systems, teams can see one version of the truth and focus on execution: what needs to be built, when it needs to be built, and what will be late unless action is taken.

Making procurement proactive instead of reactive

Most shortages don’t come from a total lack of demand visibility—they come from lag time and inconsistency: wrong lead times, stale planning parameters, mismatched units of measure, suppliers shipping partials without being caught, or buyers finding problems too late to avoid expedites.

This is where an ERP system earns its keep in supply chain management. When purchasing is tied to real requirements (not gut feel), the system can drive more disciplined ordering, clearer supplier commitments, and better exception handling. You’re not just placing purchase orders—you’re managing supply risk: what’s coming in, what’s late, what’s short, and what will impact customer shipments if it doesn’t get solved now.

Bridging the gap between “the plan” and the plant floor

Supply chains often fail at the handoff between planning and execution. You can have a perfectly reasonable MRP output and still miss shipments if the shop floor can’t realistically run the schedule, if routings are inaccurate, or if WIP isn’t visible enough to know what’s actually done.

ERP supports supply chain management when it reflects production reality: capacity constraints, labor availability, setup time, yield, and the true status of jobs. The goal is to make execution predictable—so the team isn’t constantly firefighting “surprises” that were actually process blind spots.

Inventory you can trust (because it’s controlled, not guessed)

Inventory is the shock absorber of the supply chain, but it’s also one of the biggest sources of hidden cost—especially when the system inventory can’t be trusted. If the ERP says you have it but the rack doesn’t, you lose time, miss builds, and expedite. If the rack has it but the system doesn’t, you overbuy and carry excess.

A supply-chain-ready ERP enforces the basics that prevent those outcomes: location control, scanning discipline where it matters, cycle count processes that actually correct root causes, and traceability when required (lot, serial, container, heat, etc.). This is what keeps inventory from becoming a guessing game—and makes planning outputs credible enough to run the business on.

Shipping performance lives or dies on compliance detail

This is the part many “generic” ERP conversations skip: the dock is where supply chain credibility is earned. It’s also where noncompliance becomes expensive—especially in automotive, where labels, ASNs, pack rules, ship-to requirements, and schedule adherence can directly impact scorecards and chargebacks.

A true operational hub connects shipping to the requirements that triggered the shipment in the first place, so teams don’t have to manually stitch together what was ordered, what’s allowed to ship, how it must be packed, and what data must be transmitted to get paid cleanly. When an ERP system in supply chain management is doing its job, the shipment process is controlled, verified, and repeatable—not dependent on tribal knowledge.

Visibility that leads to decisions (not dashboards that look nice)

Finally, visibility only matters if it changes behavior. The best ERP-driven supply chains use reporting and alerts to manage exceptions: what changed, what’s at risk, what’s drifting from standard, and what needs attention before it becomes a late shipment or an expedite.

That’s the difference between “having data” and managing performance. Executives care about OTIF, lead time, inventory turns, and margin because those metrics are the downstream result of a thousand small execution decisions. ERP helps when it creates a closed loop—where the business can see issues early, correct them quickly, and prevent repeats.

How to choose an ERP system in supply chain management: three operating models (and how to pick yours)

When people search “what is ERP in supply chain management”, they’re usually trying to answer a more practical question: What system should “own” supply chain execution—and how do we stop demand, inventory, production, and shipping from drifting out of sync? The fastest way to get clarity is to choose the operating model first (how work flows end-to-end), then evaluate software second (which platform supports that model without constant workarounds).

Operating model #1: One ERP runs the supply chain end-to-end

This is the “single operational hub” approach: the ERP system in supply chain management is where demand is captured, materials are planned, production is scheduled, inventory is transacted, and orders are shipped and invoiced. It’s a strong fit when your biggest challenge is visibility and coordination across departments—because one database, one set of masters, and one workflow reduces handoffs, duplicate entry, and the “two versions of the truth” problem.

If your team is spending hours reconciling spreadsheets, rekeying orders, or chasing inventory accuracy, a unified ERP system in supply chain is often the simplest way to stabilize execution and improve OTIF performance.

Operating model #2: ERP as system of record + a supply chain execution layer

In many manufacturers—especially automotive suppliers—ERP is still the financial and master-data backbone, but you add a purpose-built layer for the supply chain execution details that drive customer scorecards. This is common when the plant is running fine operationally, but performance gets hit by EDI volatility, labeling requirements, ASN accuracy, scan verification, and customer-specific shipping rules that a generic ERP handles only with heavy customization.

In other words, you keep ERP as the “book of record,” but you strengthen the execution edge where errors and chargebacks typically happen—so daily shipping, packaging, and compliance can run at production speed without breaking every time a trading partner changes a rule.

Operating model #3: ERP + specialized planning/analytics (control tower)

Some organizations don’t struggle with transactions—they struggle with planning under uncertainty: demand swings, constrained capacity, supplier risk, long lead times, or multi-site complexity. In these cases, the ERP system in supply chain management still matters (it provides clean, trusted data), but the “decision layer” may include APS/S&OP tools, advanced forecasting, or analytics dashboards that sit above ERP.

This model can be powerful, but it only works when ERP data integrity is strong—otherwise, advanced planning just turns bad inputs into confident-looking bad outputs.

A practical sizing guide: match the model to complexity, not hype

A useful way to avoid overbuying (or under-solutioning) is to align the operating model to your scale and execution complexity. Smaller-to-mid suppliers often benefit from a single, tightly integrated ERP backbone because the fastest ROI comes from eliminating disconnected processes. As plants multiply, OEM/customer mandates increase, and EDI/label/ASN variability becomes a daily reality, many teams shift toward an ERP + execution layer strategy to protect shipping performance and compliance without forcing massive ERP customization. (If you want a CRM-friendly breakdown of supplier revenue tiers and what typically changes operationally as suppliers scale, use this reference.)

How an ERP system keeps the supply chain synchronized (in the real world)

The schedule changes at 10 a.m.—your ERP should absorb it

If you’re asking what is ERP in supply chain management, the most practical answer is this: it’s the system that takes changing demand, available supply, and capacity constraints—and turns them into coordinated actions across purchasing, production, inventory, and shipping. In a modern environment, forecasts move, releases shift, and priorities change daily. An ERP system in supply chain management has to handle that volatility without creating chaos (or relying on heroics) by updating demand signals, recalculating material needs, adjusting schedules, and keeping every department aligned on the “current truth.”

This is also where many teams discover the difference between having software and running a controlled process. If the system can’t quickly reflect changes and cascade them into the right downstream actions, you get the classic ripple effects: material shortages, expedite fees, excess WIP, missed shipments, and service levels that look fine on paper but fail on the dock.

Inventory is the truth serum (and it’s where most plans break)

In any ERP system in supply chain, inventory accuracy is the foundation for everything else—MRP, production scheduling, customer promise dates, and even financial performance. When inventory is wrong, the system doesn’t just “get a little off.” It produces confident-looking plans that can’t be executed. That’s why supply chain results improve fastest when the ERP enforces disciplined execution: location control, real-time transactions, cycle counting, and (where required) lot/serial traceability.

When inventory integrity is strong, you can reduce safety stock without increasing risk, improve inventory turns, and stop paying for avoidable expediting. When it’s weak, teams end up buffering everything “just in case,” which quietly drains margin through carrying cost, obsolescence, and wasted labor.

Procurement shouldn’t “guess”—it should commit (with context)

ERP-driven procurement works when it turns planning into reliable commitments: the right buy quantities, the right timing, and the right supplier constraints. That means lead times, order policies, minimums, pack quantities, and supplier performance data have to be clean enough for the system to generate sensible recommendations—and visible enough for buyers to intervene when reality changes (allocation, delays, quality holds, freight disruptions).

The payoff isn’t just fewer shortages. It’s fewer last-minute surprises, more stable production schedules, better supplier conversations (“here’s what changed and why”), and better working capital control because you’re not buying “extra” to compensate for planning uncertainty.

Shipping is where your scorecard is written

Most companies think of shipping as the final step, but it’s where the supply chain gets graded—especially on OTIF, chargebacks, and customer compliance. A strong ERP execution flow ties together pick/pack/ship, packaging rules, shipment validation, and the documents customers require. In automotive and other high-compliance supply chains, that often includes tight alignment across releases, shipping paperwork, and electronic confirmations like ASNs.

This is one place generic “we can print a label” functionality often falls short. Automotive customers commonly communicate requirements through EDI schedules and transactions (for example, shipping schedules and releases), and many environments require precise handling of customer reference data and cumulative tracking to avoid disputes and preventable rejections.

Leaders don’t need more reports—they need early warnings

Finally, the best ERP-enabled supply chains don’t just “record what happened.” They surface what’s about to go wrong—before it hits OTIF or triggers chargebacks. That’s where exception management becomes a real differentiator: alerts for demand spikes, late inbound materials, capacity overloads, inventory discrepancies, and shipping risks, all routed to the right owners with clear next actions.

When this works, performance improvements show up quickly in the metrics executives care about: service levels, lead time, inventory turns, schedule stability, and margin protection. And instead of running your business through spreadsheets and fire drills, the ERP becomes the operational hub that keeps execution aligned—even when conditions change.

Conclusion

An ERP system in supply chain management is no longer just a system of record—it’s the operational hub that connects demand, inventory, production, purchasing, and shipping into one controllable flow. In this article, we covered what is ERP in supply chain management, the end-to-end processes it must unify, and why the real performance gains come from data integrity and execution discipline (not a longer feature list). And for automotive suppliers, we emphasized the “make-or-break” layer many generic platforms struggle with: EDI-driven releases, AIAG-compliant labeling, ASN validation, and CUM tracking—because that’s where OTIF, chargebacks, and customer scorecards are won.

If you’re evaluating an ERP system in supply chain, prioritize a solution (or an ERP + automotive execution layer) that enforces customer rules at the dock and on the shop floor—not just in reports—and if you’d like a practical roadmap, AIM can help you identify gaps and build an audit-ready path forward with AIM Vision ERP, AIM AutoSys, or AIM AutoCOR.

Ready to turn supply chain trends into real results?

If you’re evaluating how well your current ERP supports real-world automotive execution—from EDI releases through compliant shipment—this is where a focused assessment can uncover hidden risk and improvement opportunities.